More politicians would benefit from listening to young Australians’ valid and pressing political concerns.

–Hannah Mansfield

Young Australians, especially those under eighteen, are becoming less interested in traditional politics. When you look at our politicians, it’s easy to see why.

The average age of a Federal Government minister is fifty-one, and they’re most likely to be rich white men with two homes and a law degree. Meanwhile, the average Australian teenager is still dependant on their parents and studying full time.

But young people are stepping up to take action on political issues. Compared to other age groups, they’re more likely to be politically active when it comes to causes that they care about, rather than political parties. Boycotting, signing petitions, and even making street art can be considered political acts.

My Honours year at Deakin University focusing on youth citizenship surrounding the 2019 School Strike for Climate.

Young Australians understand politics in different and unique ways, seeing themselves as distinct political citizens.

But the question remains: do our federal politicians even notice?

The 2019 School Strike for Climate

In September 2019, following the lead of climate-activist Greta Thunberg, school students Australia-wide organised massive protests calling for greater climate action.

An estimated 300,000+ students and adults attended one of the largest public demonstrations in the country since the 2003 anti-Iraq War marches.

Their movement was big on social media, where they used platforms such as Instagram and Facebook to promote these protests to their 100,000+ followers.

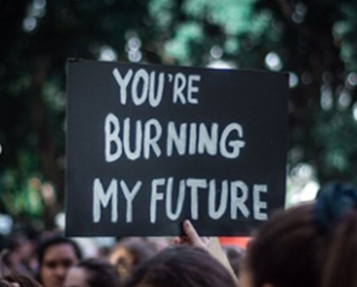

Caption: Young Australians are angry with the Prime Minister. Source: Instagram

The kids are not alright

My research analysed the 58 Instagram posts of School Strike for Climate Australia (SS4C) from August to October 2019, to gather information on how young people think about, act on and articulate their politics.

The results were surprising. Instead of trying to appear older and more powerful, SS4C actively endeavoured to appear more child-like. They drew strength from their innocence.

For example, when primary-school-aged children carry handmade signs asking the government to protect the environment, it becomes a difficult message to refute politically.

But they were also angry, especially with Prime Minister Scott Morrison. For these young Australians, Morrison represents how outdated politics is, reliant on the fossil fuel industry for capital.

Signs stating that Morrison has ‘no brain’ shows an innate distrust in formal politics. This is heightened when you look at the country’s voting age.

In Australia, although it’s legal for sixteen-year-olds to get married, pay tax, work full time, or serve in the army, they’re still not able to vote until they turn eighteen.

Multiple posts of young people holding megaphones and speaking in front of huge crowds showed them ‘speaking up’ and refusing to stay silent. They have more of a voice on the streets than they do in the Australian parliament.

Further, they were creative and funny. They advertised sign-making workshops, promoted wearing yellow to support the cause, and encouraged written jokes on placards for the march.

Some politicians heard the message, but not all listened

To compare the pair, from the same months in 2019, I pooled statements made in parliament that directly addressed the School Climate Strikes.

The results were divided.

Out of the twenty statements, nine of them involved Australian Greens representatives.

Green’s senator Steele-John was the student’s biggest advocate, even moving that the Senate support the Climate Strikes.

Steele-John, along with Labor MP’s Chester, Mitchell, and Payne, all directly acknowledged students from their electorate. These politicians committed to bringing young Australian’s voices into parliament, when they lacked the agency to be there themselves.

Yet some still relied on old stereotypes to gain political points. In a speech to parliament, Labor MP Thistlethwaite called the Liberal party ‘infantile’ and ‘childish’. It was an odd way to defend the children who were marching, by referring to the other party as child-like.

Liberal MPs were more likely to criticise the students.

National MP, Keith Pitt, said, ‘I recall, as a schoolchild, that any opportunity to get out of school was a great opportunity.’

Later, political shock jock and then-Liberal MP, Craig Kelly, stated that students only attended the march because of their ‘desire to conform and fit in with the crowd’.

And what about the Prime Minister that the students were so angry with? Well, he didn’t appear to comment on the strikes at all in parliament.

Although Morrison had previously commented on the strikes, his silence in parliament was deafening.

Caption: Young Australians should be able to vote at a younger age. Source: Instagram

Politicians needs to listen to young people

There is a big divide in Australia between how young people see themselves as political citizens and how politicians view them.

As young people are more disillusioned with the Australian government, their trust in democracy falls.

A promising policy change would be the bill proposed to let those aged sixteen and seventeen vote on a voluntary basis. However, there needs to be greater political will before this bill might ever pass successfully.

In the meantime, with a 2022 Federal Election looming, more politicians would benefit from listening to young Australians’ valid and pressing political concerns.

Hannah Mansfield recently finished her Honours year at Deakin University focusing on youth citizenship surrounding the 2019 School Strike for Climate.